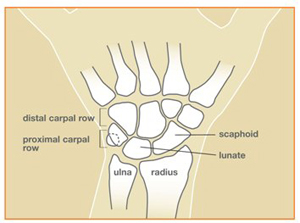

The scaphoid bone is one of the eight small bones that comprise the

wrist joint. The two rows of small wrist bones act together to allow the

wide variety of wrist positions and motions that we take for granted.

The scaphoid bone spans or links these two rows together and, therefore

has a special role in wrist stability and coordinating wrist motion (see

Figure 1).

The scaphoid bone is vulnerable to fracture because of its position

within the wrist and its role in wrist function. When the scaphoid bone

is broken, it may not heal properly because it has a very fragile blood

supply. Scaphoid fractures that do not heal are referred to as a

scaphoid non-union. Ultimately, scaphoid non-unions can lead to loss of

wrist motion and eventual wrist arthritis.

Patients with a scaphoid non-union usually present with a history of

previous wrist injury, especially a fall onto an outstretched wrist.

They will typically have pain along the thumb side of the wrist and may

also have diminished wrist mobility, particularly wrist extension.

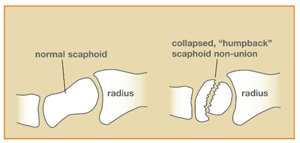

Scaphoid fractures and non-unions are usually confirmed by x-rays of the

wrist (see Figure 2A and 2B). In many cases, special x-ray tests are

also used to decide the best treatment approach. A CT scan is helpful to

check for collapse of the scaphoid on itself, resulting in a bend in the

bone, which is called a “humpback” deformity (see Figure

3).

Scaphoid non-unions may also develop a problem called avascular

necrosis. Avascular necrosis occurs when part of the scaphoid bone dies

because of the loss of blood flow. This can eventually result in

fragmentation and the collapse of the bone. Its presence also makes

repair of the scaphoid much more difficult. An MRI scan can be helpful

to check for avascular necrosis (see Figure 4).

Treatment of a scaphoid non-union is dependent upon a variety of

factors. Once a scaphoid fracture has failed to heal, a relatively

predictable pattern of degeneration within the wrist generally occurs,

although the time frame is variable. In most cases, the scaphoid

eventually collapses, which results in a change in wrist mechanics that

leads to motion loss and arthritis. Depending upon the stage of this

process at which the non-union is recognized, various treatment

alternatives exist. In cases without significant arthritis, surgery to

restore scaphoid alignment and heal the bone is preferred. This usually

requires placement of a bone graft and some type of internal bone

fixation, such as pins or a screw (see Figure 5).

Scaphoid non-unions with avascular necrosis present special challenges

to healing since part of the bone is dead. Recent techniques using bone

grafts with an attached vessel to maintain blood supply (vascularized

bone grafts) have improved our ability to heal these difficult

conditions (see Figure 6).

Finally, in cases with established arthritis or failed reconstructive

efforts, surgery to heal the scaphoid is often no longer an option. In

these cases, surgery is tailored towards pain improvement along with

maintaining a functional wrist. Depending on the degree of arthritis,

surgery may include techniques that spare motion, such as radial

styloidectomy (removal of a local piece of arthritic bone), partial

fusion of the wrist bones, or proximal row carpectomy (removal of the

proximal row of wrist bones). If the arthritis is more widespread in the

wrist, complete wrist fusion may be needed.

Figure 1: Wrist bone anatomy

Figure 2A: X-ray of scaphoid fracture non-union

Figure 2B: X-ray of normal scaphoid

Figure 3: Diagram of normal and collapsed scaphoid

Figure 4: MRI of scaphoid fracture non-union with avascular

proximal fragment

Figure 5: Scaphoid repaired with a screw

Figure 6: Vascularized bone graft for scaphoid

© 2006 American Society for Surgery of the Hand